Majorana Fermions

A Symmetrical Theory of the Electron and the Positron (1937)

Much has been said about antimatter since its discovery in 1933. Spin-½ particles such as electrons and quarks, categorically known as fermions, come in pairs of opposite charge. An electron, for instance, is negatively charged while its antimatter doppelganger, the positron, is positively charged. Both, nevertheless, have the same mass.

But what about neutral fermions? Is it possible for a particle with no electric charge to be its own anti-particle?

These are the questions that enigmatic Italian physicist Ettore Majorana sought to address in A Symmetric Theory of Electrons and Positrons. The paper has left a deep and lasting impact on physics, introducing an avant-garde rethinking on how matter and antimatter might be related and promising far-reaching implications for high-energy physics.

Majorana’s formulation naturally leads to an elegant description of neutral particles, crucially suggesting that for particles like neutrinos, there might be no meaningful distinction between particle and antiparticle.

The Problem with Negative Energy

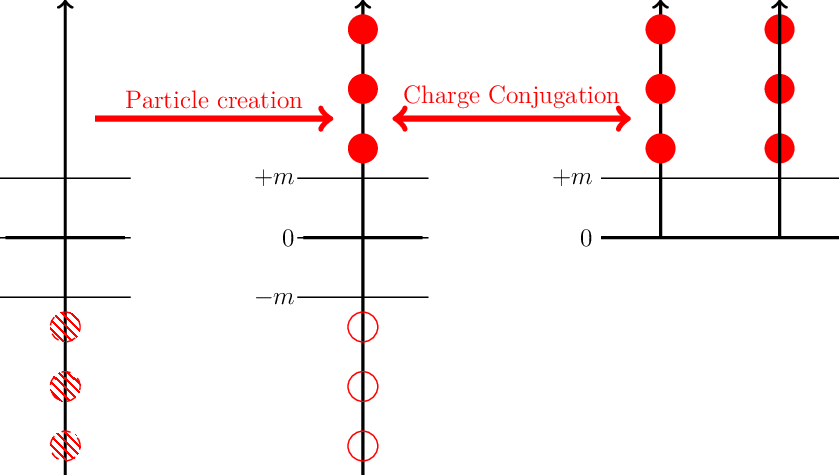

Majorana’s key idea was recognizing that it is possible to reformulate quantum electrodynamics (QED) in a way that is inherently symmetric with respect to particles and antiparticles, eliminating the need for Paul Dirac’s infamous sea of negative energy states.

In Dirac’s original theory, electrons are described by a wave equation that admits both positive and negative energy solutions. To prevent electrons from cascading into negative energy states, Dirac introduced the concept of a filled “sea” of negative energy states. Holes in this sea were interpreted as positrons.

While this idea was the first hint at the existence of antimatter and a founding principle of QED, it came with an uncomfortable asymmetry. One begins with an unphysical sea of electrons and only retrieves the symmetry between particles and antiparticles through a somewhat convoluted reinterpretation.