Quantum mechanics, a radical departure from classical physics, emerged as a powerful framework for explaining atomic and subatomic phenomena during the early 20th century. One of the key figures in this research was Erwin Schrödinger. In his work "Quantization as an Eigenvalue Problem," Schrödinger presents the foundational principles for what would become his famous equation, offering profound insights into the nature of quantum systems.

A Shift from Integer Quantum Numbers to Natural Emergence

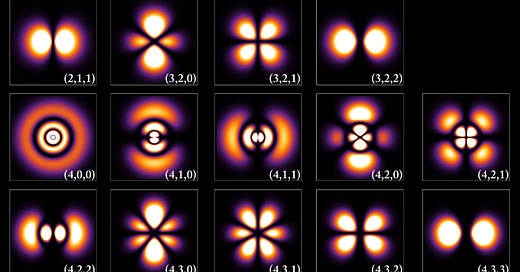

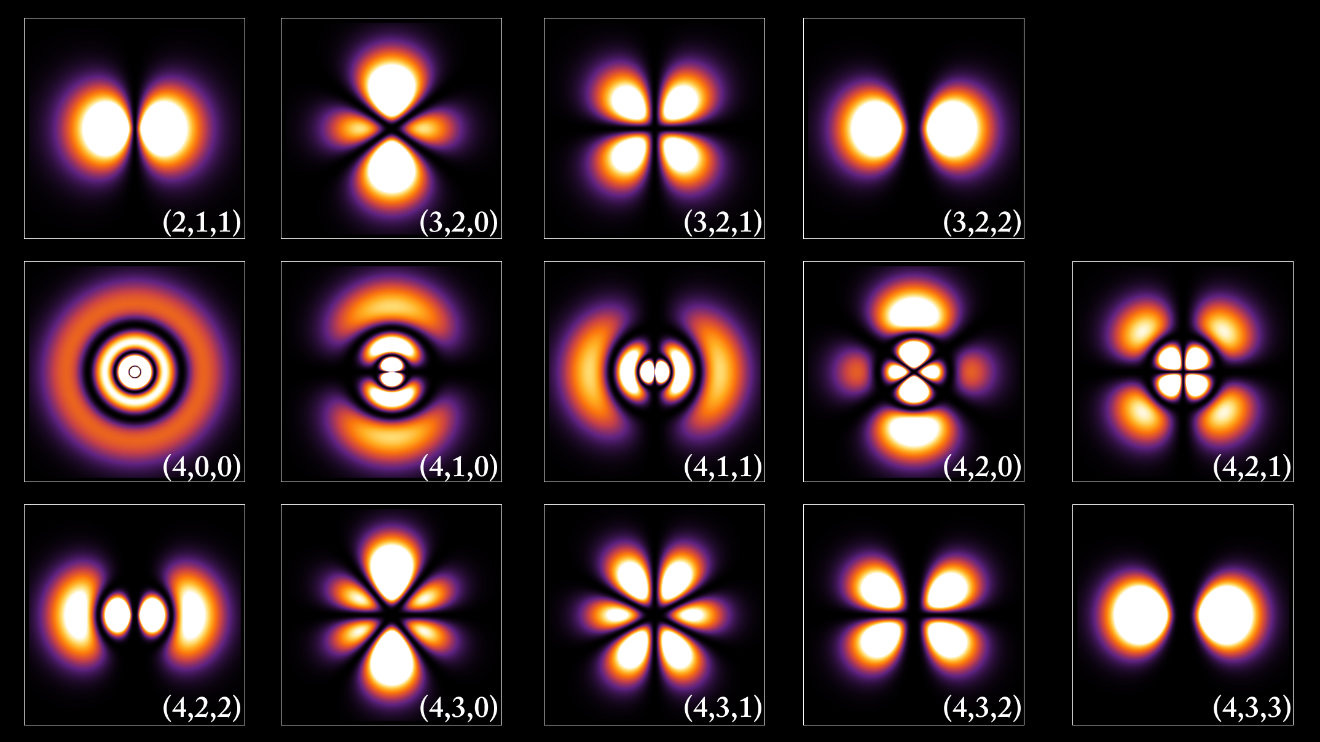

Traditionally, quantization in physics has been associated with integer quantum numbers, which are somewhat mysterious in their origin. These integers are introduced ad hoc, through the imposition of boundary conditions in systems like the hydrogen atom, to account for phenomena such as discrete energy levels. In this work, Schrödinger proposes a new approach where integer quantum numbers emerge naturally, analogous to how the number of knots in a vibrating string arises from the physical constraints of the system.

Schrödinger begins by reconsidering the quantization conditions of a hydrogen atom. Instead of invoking the direct imposition of integer values, he introduces a variational principle based on the extremum of a quadratic form involving a new function, denoted as ψ. This function is the key to Schrödinger’s formulation, as it represents a solution that is finite, single-valued, and twice differentiable over the entire configuration space.