Prime Mover

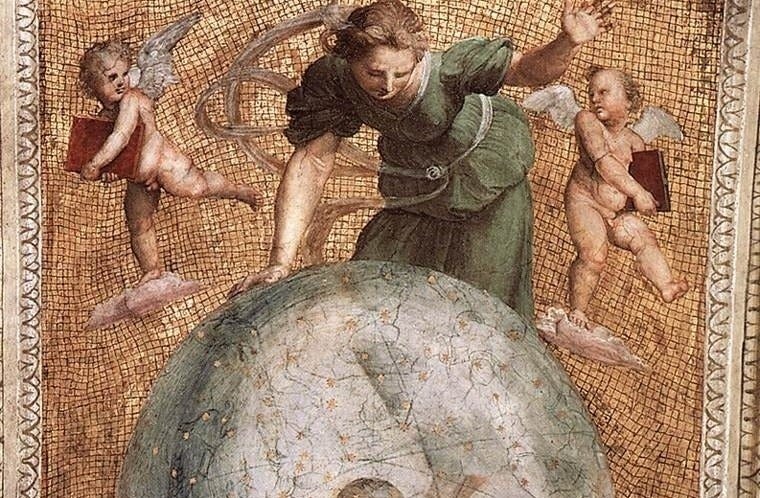

The physical genesis of causality

When one speculates on the creation of the universe, quandaries and paradoxes abound. Notwithstanding the concept of a multiverse, the universe appears to be all that is—endless light-years of stars, dust, and interstellar voids. What could have brought the cosmos into existence if it already contains everything?

Without the veil of mysticism or religion, such a question seems utterly impenetrable. Even posing it could be a foolhardy endeavor.

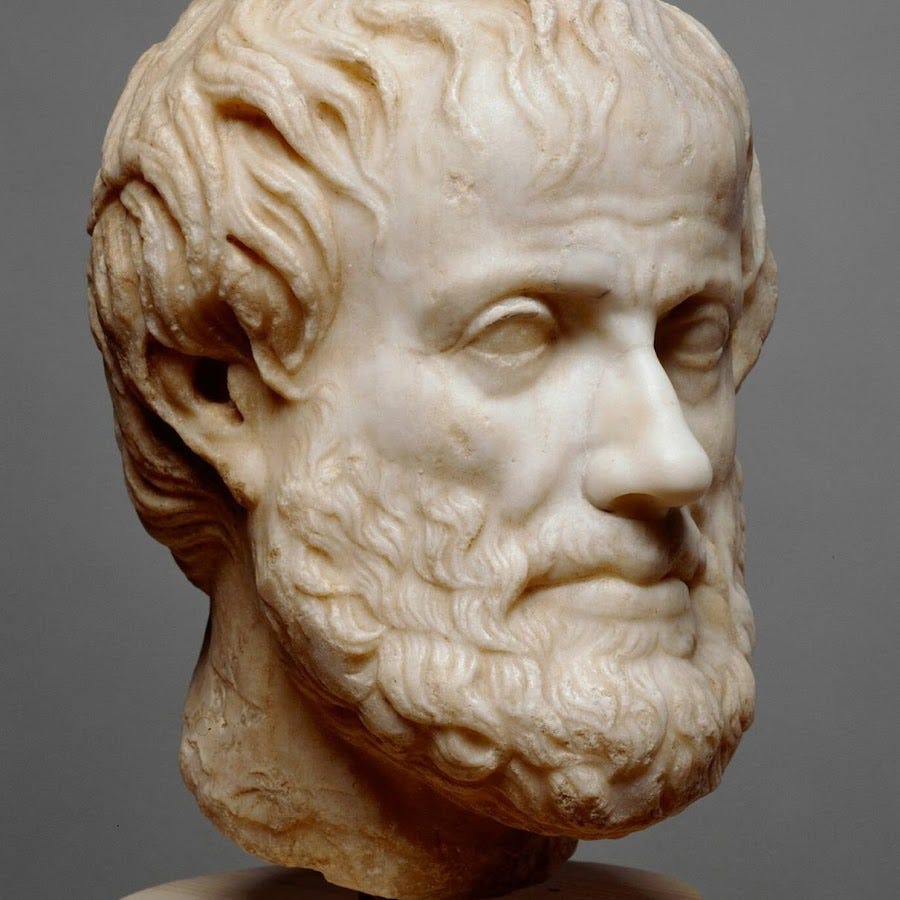

The daunting nature of the problem, however, has only served as motivating fuel for some of history’s greatest intellects. In a previous post, we talked about one attempt to resolve the mystery of existence in the writings of Gottfried Leibniz. Yet, his arguments borrow many presuppositions from a long line of thinkers going all the way back to antiquity. Chief among them was the great Aristotle.

In this regard, he is best known for founding the idea of an unmoved mover who would be responsible for initiating all motion in the universe while remaining unmoved. In Book VII of Aristotle's Physics he asserts,

Since everything that is in motion must be moved by something, let us take the case in which a thing is in locomotion and is moved by something that is itself in motion, and that again is moved by something else that is in motion, and that by something else, and so on continually: then the series cannot go on to infinity, but there must be some first mover.1

While this may seem like a straightforward argument, we must go deeper into the terminology of Ancient Greek philosophy to truly grasp what is being said here. For Aristotle, movement meant much more than simply a translation of position through space, though it can also encompass this signification.